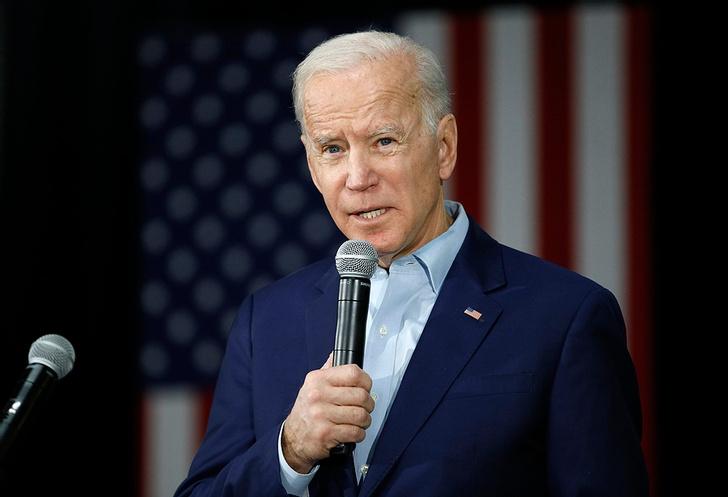

On July 9, President Biden issued a mammoth executive order (EO) focused on increasing competition that included everything from bringing back net neutrality rules to asking the Food and Drug Administration to investigate cheaper pharmaceutical imports from Canada.

The July 9th order also contained four areas relevant to the IoT: broadband, devices, privacy, and antitrust. Broadband is my favorite, because without access to high-quality, cheap broadband there is no internet of things.

With that in mind, I’m stoked that the Biden administration is directing the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to bring back the net neutrality order from the Obama years. The Biden EO also asks the FCC to continue bringing to fruition a “broadband nutrition-style” label that would detail all of the potential charges associated with monthly broadband access. Indeed, Consumer Reports issued a study prior to the pandemic noting that almost a quarter of a consumer’s cable bill was composed of fees. The label would require that all of those fees, plus relevant details about the service itself, be easy for a consumer to find when reviewing their options.

Finally, the broadband section of the EO asks the FCC to limit sky-high termination fees. These rules mostly affect consumer broadband, which I think is important, especially as consumers focused on making the most of their smart homes look for higher-quality Wi-Fi while still paying monthly charges for ISP equipment they may not be using.

On the net neutrality side, I think it’s important to prevent ISPs from preferencing their smart home services over those provided by outside companies. And as 5G ushers in an era of network slicing for enterprise and industrial customers, I’m interested to see how net neutrality rules may or may not apply. After all, network slicing is the definition of prioritized content, although I think in this case it’s merited.

Outside of broadband, starting with devices, there are two elements that matter. The first is a big one: encouraging the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to issue rules against anti-competitive restrictions that prevent repairs to devices by independent repair shops or the device owners themselves. These rules are aimed at companies like Apple, which make it difficult to access the insides of devices in order to repair them and which, for a long time, limited supplies to independent repair shops so those shops couldn’t access the parts they needed.

The other order relates mainly to agriculture, although it could have an impact on connected cars or other connected machinery as well. It directs the FTC “to limit powerful equipment manufacturers from restricting people’s ability to use independent repair shops or do DIY repairs — such as when tractor companies block farmers from repairing their own tractors.” This is a direct callout to John Deere, which has been a villain of the right-to-repair market for a decade.

The rules will be controversial not only because the profits of large companies are at stake, but also because manufacturers are arguing that opening up their software or supplies for repairs can reduce the end security of the devices or allow people to bypass safety mechanisms. This may be true, but in a country like America where individual rights often trump the collective good, I find it hard to believe that a farmer who tweaks his tractor so it emits more particulates than regulations allow will end up losing this fight.

That said, as everything we buy becomes software wrapped in a piece of hardware, having access to the code and guaranteed rights to makes repairs, or to accessing particular hardware, is increasingly important.

Also on the device side, the Biden administration wants The Department of Health and Human Services to issue rules within the next 120 days that allow over-the-counter sales of hearing aids. This will open up a huge opportunity for lots of companies to combine the breakthroughs in AI, the computing power available on smartphones, and the economies of scale associated with consumer electronics to both lower the cost and improve the performance of hearing aids. The original legislation mandating this was passed in 2017, so we’ve been eagerly waiting for this to happen.

The order also provides a quick salve to those concerned about data grabs by large tech companies and those of us who worry about IoT devices ushering in a new surveillance state. But it’s a limited salve; it merely calls on the FTC to establish rules on surveillance and the accumulation of data, which is so vague as to be useless.

To be fair, however, back in 2013 the Obama-Biden administration called on the FTC to create a report analyzing the effect of data-gathering techniques and the use of data generated by the IoT for consumer harms. The report, which came out in 2015, showed a real understanding of the issues and called on Congress to pass specific laws to help. It asked Congress to create a law governing data privacy that would mandate ways device makers could help users manage their privacy, such as a privacy dashboard. The law would also suggest device makers limit the amount of time they keep user data, ask both device makers and sites to limit the data they collect and de-identify that data, and require device makers to provide some type of user opt-in and understanding of how data would be used outside of long documents that no one reads.

That still sounds good, although now I’d want a segment added in that focuses on how the data collected by devices could be used in specific contexts, such as in insurance markets, law enforcement, and education.

Finally, the bulk of the order deals with antitrust issues associated with the big tech giants. It contains a lot about online marketplaces in particular, namely preventing Amazon and other online retailers from using data about the third-party devices sold on their platform that could then be used to launch a competing device and prioritize its sales on the same platform.

The order also asks the FTC and other relevant agencies to take a closer look at prospective M&A activity, as so far, M&A in the tech world has largely been used to buy startups to fold their technology into the acquiring companies or to simply shut the startups down altogether. For startups, it’s worth being aware of a potential shift in this dynamic as companies evaluate who their potential acquirers and partners might be. Closer scrutiny by federal agencies might also mean deals will take longer to come to fruition or will only do so with more onerous constraints.

There’s a lot here to like as a consumer, and even as an innovator (for example, cheaper, better broadband will open up more opportunities). But as these rules are enacted there will be a period of adaption for many businesses — and some outright shifts in business models.