5G bargain hunters could do worse than head to Japan. Rakuten Mobile, the nation's newest mobile operator, charges just $30 a month for a 5G service, about 70% less than its rivals. Such a massive discount is possible, says Rakuten, because its state-of-the-art network is much cheaper to build and operate than a traditional one.

The sponsors of open RAN, a radio access network technology at the heart of Rakuten's innovation, make a big deal about such savings. One developer says a telco customer expects to save between 30% and 40% on capital expenditure and around 30% on operating costs. Tareq Amin, Rakuten Mobile's chief technology officer, puts his total network savings at 40% on capex and 30% on opex.

"I believe radio spend, conservatively speaking, is anywhere between 60% and 70% of the total capex and other stuff is almost irrelevant," he said when recently asked to cite open RAN's specific contribution. "For us, 60% of the savings come from radio."

But his bold greenfield project has some high-profile skeptics. Neville Ray, Amin's counterpart at T-Mobile US, confessed doubts about the open RAN cost argument at a recent industry conference. "It's not ready for prime time for us," he said. "I'm not going to go and chase a bunch of capital efficiencies which I'm not sure exist at this point."

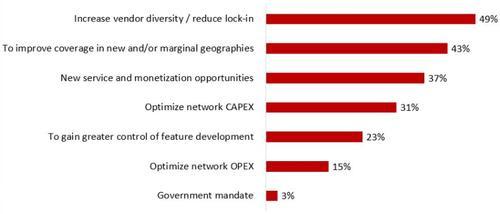

Other service providers are also dubious, according to Gabriel Brown, a principal analyst with Heavy Reading. "Most operators agree the capex (and especially opex) savings aren't there yet for open RAN," he recently tweeted. Just 31% of telco respondents to a Heavy Reading survey identified capex as a motivation for open RAN initiatives. And only 15% cited opex.

Motivation for open RAN

Barely moving the needle

Skepticism is warranted. Awkwardly, for its advocates, open RAN looks unlikely to have much impact on pricing power or profitability, even if the cost optimists are right. Yes, operators invest plenty of money in their radio access networks. But they spend a lot more elsewhere.

Figures supplied by Stefan Pongratz, an analyst with market-research firm Dell'Oro, highlight the disparity. Annual spending on radio access networks typically amounts to between $30 billion and $35 billion, he says, while overall wireless capex is usually as much as $150 billion. In other words, the radio access network accounts for only about a fifth of the total wireless bill.

Daryl Schoolar, a practice leader at Omdia, is broadly in agreement. "By my estimate, basestations are around 18-20% of total mobile capex," he tells Light Reading. His estimate is that open RAN could reduce these costs by around 20%. "The rest is labor, construction, backhaul, core network and other elements."

Much of this will be hard to chisel away. It covers physical infrastructure items such as towers, steel and cement – impervious to any technological advance that software developers can muster. Savings might be available in areas such as the mobile core and transport, but not from anything open RAN can affect. They lie outside its remit.

Even with the most generous assessment, the capex impact looks meager. Take, for instance, a mobile-only operator like Three UK, a part of Hong Kong's CK Hutchison group. Last year, accounts show, it made about £2.4 billion (US$3.2 billion) in sales and invested precisely £426 million ($572 million) in capex, putting its capital intensity at 18%, a relatively high figure in Europe's telecom sector. If all that capex were classed as wireless (which is unrealistic but convenient for this exercise), and a fifth went on the radio access network, just £85 million ($114 million) would be susceptible to open RAN.

Now assume Three managed to save as much as 40% in this domain. That achievement would shave about £34 million ($46 million) off its bill – just 1.4% of its sales. Of course, all this is entirely theoretical. As a mobile operator that is not currently expanding its footprint, Three might conceivably spend much more than a fifth of its capex on the radio access network. The point is to see Three, which currently has no plans for open RAN whatsoever, as a microcosm of the industry.

John Strand, the CEO of advisory group Strand Consult, frames open RAN capex savings in the context of average revenue per user (ARPU) and says they equate to just 1% of this ARPU figure. According to calculations he sent Light Reading, mobile infrastructure accounts for about 30% of total telecom capex, and spending on radio access networks represents between 2.8% and 3.6% of telecom ARPU. In his view, open RAN will have no impact on a sizable chunk of this investment. Capex can sometimes include fees for installation and labor, for instance, as well as other costs associated with the rollout.

General-purpose gear and other promises

All of which raises questions about the nature of open RAN savings. Mavenir, a US cheerleader for the technology, has for years dangled the promise of a near-halving in capex from a switch to a cloud RAN. In this set-up, operators could separate hardware from software and then redesign their networks for improved efficiency. Open RAN, in the strictest sense, would boost vendor interoperability, allowing an operator to select software and components from different suppliers.

Vodafone Ireland has just concluded a small open RAN deal with Parallel Wireless, a Mavenir rival, along with several other vendors. Asked about cost savings, a Vodafone spokesperson said the injection of competition provided by new open RAN players would drive prices down. Vodafone also expects the general-purpose hardware used in open RAN networks to cost less than traditional equipment.

This has been taken for granted by the industry, as if "general purpose" means the same as "low cost." Yet traditional vendors, including Huawei and Ericsson, ship thousands of basestations each year and enjoy economies of scale that open RAN – with its miniscule $252 million in revenue this year, according to Schoolar's latest estimates – simply cannot match. What makes open RAN kit any cheaper on a like-for-like performance basis?

Nothing, insists Ericsson. "It would be sad if we build something that is only for one purpose and we cannot do it more cost effectively than with general-purpose hardware," said Per Narvinger, the head of product area networks for the Swedish vendor, during a previous conversation with Light Reading.

Even so, the out-of-the-box systems sold by the likes of Ericsson would probably carry a price premium over open RAN parts that require assembly, according to Omdia's Schoolar. "Compare it to going to a store and buying a Mac laptop, versus buying a bunch of components and building it yourself," he says.

Want to know more about 5G? Check out our dedicated 5G content channel here on Light Reading.

As for the injection of competition that Vodafone anticipates, that is not something Ericsson or other big vendors are likely to welcome. But is it a realistic long-term prospect? Alcatel, Lucent, Motorola, Nortel and Siemens are among history's sellers of radio access network products, and yet none survived the market's harsh conditions as standalone firms. Operators were partly culpable, opting for low-cost Chinese goods that Western firms could not undersell. As recently as 2015, telcos had no issue with consolidation. Not a single operator complained that year's proposed takeover of Alcatel-Lucent by Nokia would hurt competition, according to the European Commission's judgement on the deal.

Future consolidation could thwart efforts to increase vendor diversity, which topped Heavy Reading's recent poll about the motivation for open RAN initiatives. But open RAN provides no guarantee that consolidation will not happen again. If the backlash against Huawei benefits Ericsson and Nokia while open RAN is still immature, the Nordic firms will be in a stronger position to buy firms that become a challenge.

Extra hassle?

If the case for capex savings is tough to defend, the one for lower opex is even more so. Indeed, a prevailing industry concern is that a properly multi-vendor network could bring all sorts of operational complexity and hassle that operators using just one or two suppliers never see. It might even require the management services of a systems integrator. None of that sounds cheap. And the prospect of systems integrators as the new powerbrokers will not appeal to operators already worried about supplier "lock-in."

Savings on the capex side might even inflate the opex bill, says Schoolar, referring to his example of someone buying computer components in preference to a finished Mac. "One was designed to be tightly integrated and have every part selected to work together, versus you selecting a bunch of best-of-breed parts that may or may not be fully optimized to work together," he explains. "Money saved on buying individual parts could be time lost putting it together and getting everything to work properly."

As with capex, much of the opex bill will be off limits to open RAN. This is harder to calculate than for capex, but Vodafone Group's total operating costs of nearly €41 billion ($49.4 billion) last year will certainly not drop by 30% because of open RAN or any other "softwareization." They include huge investments in sales and marketing, where open RAN seems to have little if any relevance. At some operators, up to a quarter of revenue is spent on these activities, according to Strand.

Mobile results at Rakuten

Rakuten is not a sensible comparison for most operators of brownfield networks. It remains loss-making, while in construction mode, and relies heavily on automation and simplified designs outside the radio access network. In that area, specifically, savings are partly the product of hard bargaining by Amin and a cozy, government-endorsed relationship with NEC, a local vendor, that operators elsewhere could not easily replicate. Working as a system design house for Rakuten, NEC is building to a profitability target that Amin deems appropriate.

Perhaps savings are subordinate to the mission of fomenting a more diverse supplier market. Success would make operators less reliant on a few giants and their technology roadmaps. It could spur innovation, aid service launches in hard-to-reach communities and even unlock opportunities in the enterprise sector of the market. Just do not take lower costs as a given.