In the next eight or nine years, if the wheels of the mobile industry's upgrade cycle keep turning at the same pace, people will start to use a technology called 6G. Nobody yet knows what it will do. The dullest possibility is that 6G continues the tradition of boosting network speeds. The wackiest is that it creates virtual reality worlds where people can experience smell, taste and touch as well as sight and sound. France's Orange wants a greener system. Others think another global standard is not even feasible in a world of clashing superpowers.

The latest suggestion is that 6G will take full advantage of open RAN. This trendy concept is designed to improve interoperability so that one vendor's radios can be used with another's network code, something not easy in today's "closed" networks. It would decouple hardware from software (virtualization), placing heavier reliance on general-purpose equipment, and allow operators to architect their networks differently. The hope is that it will boost competition, providing alternatives to today's powerful kit vendors, and bring other business benefits.

Ericsson CEO Börje Ekholm thinks open RAN will be integral to 6G.

But the recent prediction about open RAN and 6G comes from one of those big vendors. "For sure, it will be a fundamental part of 6G solutions," said Börje Ekholm, the CEO of Sweden's Ericsson, while addressing analysts on his company's second-quarter earnings call last week.

Despite the potential threat to its own business, Ericsson needs to show willingness simply because its biggest customers are now demanding support for open RAN technology. Some of the world's largest operators, including Vodafone in the UK, have already begun rolling out open RAN networks for their 4G and 5G services. Refuse to adapt and Ericsson would have more to lose.

Open RAN lockout

Probably not in 5G, though. For all the excitement, analysts at Dell'Oro and Omdia (a sister company to Light Reading) think open RAN will – by the mid-2020s – have captured only about one-tenth of a total market for radio access network products worth between $30 billion and $35 billion annually.

So far, the operators investing in open RAN seem mainly determined to skirt Ericsson and Nokia, probably because sticking with the old guard would defeat one purpose of the new technology. Only one publicly announced deal has featured a Nordic vendor. That is the high-profile Rakuten deployment in Japan, where Nokia is providing some 4G radios.

In developed markets, most operators are now signing multi-year contracts for traditional 5G products supplied by the Nordic firms. Introducing open RAN into the mix before these have fully depreciated would mean incurring additional expense and risk disruption. A desire to avoid that could effectively lock open RAN out of the main macro network until the second half of the 2020s.

BT's Howard Watson does not see a major role for open RAN until the late 2020s.

Regardless, there is telco skepticism that open RAN will be good enough before then. The UK's BT is one European incumbent that does not envisage using it until "the back end of the decade," in the words of Howard Watson, its chief technology officer. Quizzed by Telecoms.com, Light Reading's sister publication, at a recent press conference, he denied this would leave BT at any kind of competitive disadvantage to Vodafone.

"We will continue to look at open RAN in other areas like small cells and some potential rural deployments, but we will focus on ensuring it is competitively ready for large-scale urban and that all the critical functions we need for the emergency services network are in place," Watson explained.

More than one 6G

The specifications that underpin open RAN are developed by a group called the O-RAN Alliance. These are essentially fixes for some of the important interfaces that link different parts of the radio access network – designed by either the 3GPP, the main 5G standards group, or its members. The O-RAN Alliance's open fronthaul interface, for example, is intended to be a fully interoperable modification of CPRI, a maligned technology owned by Ericsson, Huawei, NEC and Nokia. Unlike CPRI, open fronthaul would not force operators to buy radios and baseband products from the same supplier – or so the O-RAN Alliance claims.

The O-RAN Alliance, then, lives in the 3GPP's shadow, making use of its bigger property and sometimes grumbling about it like a surly neighbor. At the same time, there is known to be concern the O-RAN Alliance might intrude on bits owned by Huawei. The Chinese vendor is a long-standing member of the 3GPP, offering its patents to other members on FRAND (fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory) terms. Unlike the other big kit vendors, though, it has not signed up to the O-RAN Alliance's own FRAND licensing agreement. Conceivably, it could sue members of that group found to be squatting on its turf.

Without starting from scratch, ensuring open RAN is a "fundamental part of 6G solutions" would probably mean extending the 3GPP's territory to encompass the O-RAN Alliance. This would calm nerves about possible legal challenges, but it could throw up other problems. For one thing, smaller vendors worry they would not be heard inside a 3GPP dominated by large companies, according to John Baker, the senior vice president of business development for Mavenir, a US software company and O-RAN Alliance member.

"What you have is a way for those smaller voices to play a part in the development of mobile technology, whereas in 3GPP they would just be sat upon and ruled out," he told Light Reading during a conversation last year. "What you have is another set of IP [intellectual property] creation going on outside that process, which in reality is all good."

Want to know more about 5G? Check out our dedicated 5G content channel here on Light Reading.

Even if the big kit vendors fully embrace open RAN for 6G, bundling the O-RAN Alliance into the 3GPP would look geopolitically counterintuitive. Both Ericsson and Huawei have sounded worried in recent months that fissures between China and the US in the equipment sector could extend into the standardization process. The global 5G standard could be succeeded by two or three regional ones, taking mobile back to the days of 3G. If this were to happen, it would endanger both the 3GPP and the O-RAN Alliance as multinational groups.

Questionable as they may be, Huawei's claims to 5G patents leadership show it is now one of the loudest voices in the 3GPP. And while it does not participate in the O-RAN Alliance, there are dozens of other Chinese members. The smaller group was formed in 2018 when the xRAN Forum, a US and European group, merged with China's C-RAN Alliance. Just three years later, that no longer seems like a marriage of convenience. Yet Chinese membership of the O-RAN Alliance has grown to more than 40 companies, according to analysis carried out by Danish advisory firm Strand Consult. They include ZTE, a state-backed rival to Huawei, and China Mobile, a state-controled operator. Bar the US, no other country is this well represented.

Jaded operators

6G means equipment makers will possibly have to settle for fiefdoms and smaller addressable markets, giving up the global mobile empire. It is perhaps an even scarier prospect for operators, who would face higher prices if their vendors lost access to global economies of scale.

There still appears to be some hope that new mobile generations stop appearing, although it seems increasingly forlorn. "We want to make a return for shareholders but also so we can invest in 6G and 7G if it comes along," says Neil McRae, BT's chief network architect. "Hopefully it doesn't, but it probably will."

Jadedness is understandable. The deployment of 5G is turning out to be a very costly and time-consuming process, and no operator has enjoyed much of a sales boost so far. Two years after it launched services, EE, BT's mobile division, covers just 40% of the UK population, compared with 90% at the same stage of the 4G rollout.

The need for new and expensive equipment is partly responsible, according to Paul Rhodes, an open RAN and 5G principal consultant for World Wide Technology, a systems integrator. The 5G "massive MIMO" panels, especially, have necessitated investment in "the new 20m street-works poles which we're now seeing," he commented in a recent LinkedIn post. Boxes have had to be "deployed at the top of masts by crane and cherry-picker, not on the ground as those 4G upgrades were."

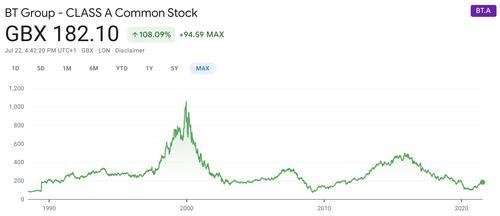

BT's share price

Source: Google Finance

Unfortunately, a 6G network based on open RAN could represent another costly overhaul. Thanks to virtualization, operators would not have to install compute products at each mobile site but could instead rely on more efficient "baseband hotels" – essentially, data centers playing host to baseband servers. This "cloud RAN," however, would demand spending on facilities as well as fiber links back to the radios. "Today, cloud RAN is in play at relatively few operators," said Gabriel Brown, a principal analyst with Heavy Reading (a sister company to Light Reading), during a recent interview. "It hasn't quite taken off because you need a lot of investment in a switched fronthaul transport network."

From a shareholder perspective, telcos are at a low. BT's own share price peaked at 1,053.24 pence sterling in late 1999. In the Internet age of 2021, it is worth just 182.40, 6% less than when BT launched 5G two years ago. Operators have retreated before the advance of the US technology giants. They are sharing networks, selling assets and trying to recapitalize infrastructure. As 6G garners attention, they are running short of options.