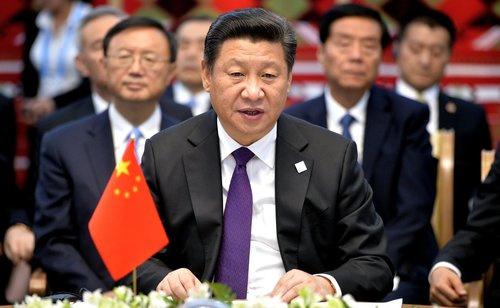

China is a master at the mafioso-like threat, softly conveyed but reinforced by immense firepower. Xi Jinping, its Godfather equivalent, currently has all barrels aimed at Ericsson, judging by the latest news. Unless Sweden backs off, the equipment vendor gets it, seems to be the message.

Sweden's crime was to have banned China's own equipment vendors – Huawei and ZTE – from its 5G market last year. Like other democracies, it is concerned about the ties between Chinese companies providing critical infrastructure and China's authoritarian and bullying government.

Its decision effectively meant the winners of new 5G spectrum licenses would not be allowed to hire either Huawei or ZTE for the construction of their 5G networks. Net4Mobility, a network jointly run by Tele2 and Telenor, promptly responded by dropping Huawei, its 4G provider, and switching to Ericsson and Nokia.

That immediately raised the prospect of Chinese retaliation. Until that moment, Ericsson had had little to say about the unfairness of other moves against Chinese vendors, including a UK government ban that has already brought two lucrative new contracts for Huawei's Swedish rival.

The action by its own government was different, as Ericsson warned in its annual report. China could respond by targeting "the economic interests of Sweden and Swedish industry, including those of Ericsson," it said. CEO Börje Ekholm began criticizing his government's move as an affront to the notion of free trade.

Xi Jinping, China's top gangster, addresses subordinates at a conference.

The risk may have grown ahead of a second Chinese tender for the rollout of 5G networks. The Global Times, a nationalistic Chinese newspaper, this week carried a report indicating Ericsson has been invited for "interview" about its potential role in the Chinese market. That interview is the "last chance for Sweden ... to carefully reconsider its China policy," says the story.

On paper, losing access to China would be worse for Ericsson than being kicked out of Sweden is for Huawei. In 5G, as in other matters, China has simply been too big to ignore. Last year, its operators reportedly bought around 700,000 5G basestations for cities and busy locations.

Even a small share of that market for Ericsson – thought to be around 11% or 12% – was a big deal. While its total revenues rose just 2% in 2020, to more than 232 billion Swedish kronor (US$22.9 billion), sales to China, accounting for 8% of that figure, were up 18%. Tiny Sweden, by contrast, represented only 0.5% of the total.

Missing out on China's second 5G tender would undoubtedly be a setback. After their 2020 equipment splurge, operators will reportedly buy another 600,000 basestations this year for less densely populated areas.

The spending commitments come with similarly huge figures. China Mobile, the country's biggest operator, plans to invest 183.6 billion Chinese yuan ($23.5 billion) in capital expenditure this year, a 1.7% increase on last year's budget. As much as RMB110 billion ($14 billion) has been earmarked for 5G.

Objectivity, China-style

The Global Times does not have a reputation for impartiality and objective reporting. In the past, it has been accused of fabricating stories and spreading fake news.

True to form, its latest report about Ericsson cites a variety of pro-Chinese and anti-Western sources, including Xiang Ligang, the director-general of the Beijing-headquartered Information Consumption Alliance. He estimates Ericsson and Nokia together account for between 15% and 20% of China's 5G market and told the paper that China had provided a "fair environment for Ericsson's operations" so far.

Yet Nokia landed no 5G deals to provide radio access network equipment whatsoever last year, and both Nordic vendors have been limited to a small share of any business in China next to the domestic suppliers. Contrast that with Huawei, which was previously allowed to capture most of the 4G network contracts in numerous European countries.

Want to know more about 5G? Check out our dedicated 5G content channel here on Light Reading.

Despite the inaccuracies and one-sidedness, there is no reason to think the Global Times, as an effective mouthpiece of the Chinese state, is wrong when it says Sweden has been told to reconsider or suffer the consequences.

Ericsson said it could not comment on the story other than to acknowledge it has been invited to carry out 5G-related tests in China. But a Chinese response to Sweden's ban was precisely the threat it outlined in its annual report. Analysts have sounded worried, pressing Ekholm on the matter during a results call last month. "I think it is concerning what we're seeing right now," he said.

Sweden is unlikely to retreat, though. It is already fighting a legal battle against Huawei, which has taken it to court in Sweden over the justification for the ban.

Net4Mobility, meanwhile, has signed 5G contracts with Ericsson and Nokia and may even have started to replace Huawei's 4G equipment (the same vendor is typically used for both 4G and 5G in a given area to ensure compatibility). An embarrassing climbdown by Sweden would send a message that China can bully Europeans into submission. Sweden's allies would be aghast.

Life after China

Disruptive and disappointing it might be, but failure to land contracts in a second 5G tender would not be devastating to Ericsson.

Even the loss of all its Chinese business would have lowered annual revenues by less than a tenth last year. And China did not even make it into Ericsson's top five sales markets in the first quarter of 2021, with number five on that list – the UK – accounting for only 3% of revenues.

Dell'Oro, a market-research firm, expects total sales of radio access network equipment to rise 3% in Europe and 2% in North America this year. Ericsson occupies a strong position in both regions.

A graver danger, perhaps, is that China's equivalent of the US Entity List – a blacklist of organizations prohibited from buying US products – cuts off Ericsson's access to a Chinese supply chain. An export control law introduced in December last year could have implications for Ericsson's ability to operate factories in China, for instance.

"We need to secure a supply flow both from a manufacturing and development perspective that is resilient to whatever happens in externalities linked to East-West relationships," said Fredrik Jejdling, Ericsson's head of networks, during a conversation with Light Reading after the publication of first-quarter results. So far, however, Ericsson has done a good job of making sure it has resources in various countries.

The main risk lies in the market for semiconductors, but not because of any Chinese government aggression. Like other technology firms, Ericsson is heavily reliant on advanced chips made only by a couple of Asian heavyweights outside China, including Taiwan's TSMC. "With some of these components, it is difficult to have a dual-vendor strategy," said Jejdling.

The doomsday scenario is a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, a territory it has long claimed as part of mainland China. Ericsson might be one of the first European companies to feel the impact of a blockade on TSMC shipments to the West. But it would be only a minor character if that invasion started a third world war. And Xi would be much more than just a threatening gangster.